Viewpoint: Why Eric Garner was blamed for dying

By Stacey Patton and David Leonard

8 December 2014

In the wake of several high-profile cases involving black Americans killed after encounters with the police, writers Stacey Patton and David J Leonard examine why blame is often shifted to the deceased.

Last week a Staten Island grand jury concluded that no crime was committed when an NYPD officer choked 43-year-old Eric Garner to death in broad daylight. Never mind what we all have seen on the video recording; his pleas, and his pronouncement, “I can’t breathe.”

So what if the medical examiner ruled it a homicide? An unfortunate tragedy for sure, but not a crime.

In fact, in the eyes of many, it was Garner’s own fault.

“You had a 350lb (158.8kg) person who was resisting arrest. The police were trying to bring him down as quickly as possible,” New York Representative Peter King told the press. “If he had not had asthma and a heart condition and was so obese, almost definitely he would not have died.”

This sort of logic sees Garner’s choices as the reasons for his death. Everything is about what he did. He had a petty criminal record with dozens of arrests, he (allegedly) sold untaxed cigarettes, he resisted arrest and disrespected the officers by not complying.

According to Bob McManus, a columnist for The New York Post, both Eric Garner and Michael Brown, the teenager shot dead by a police officer in Ferguson Missouri, “had much in common, not the least of which was this: On the last day of their lives, they made bad decisions. Especially bad decisions. Each broke the law – petty offenses, to be sure, but sufficient to attract the attention of the police. And then – tragically, stupidly, fatally, inexplicably – each fought the law.”

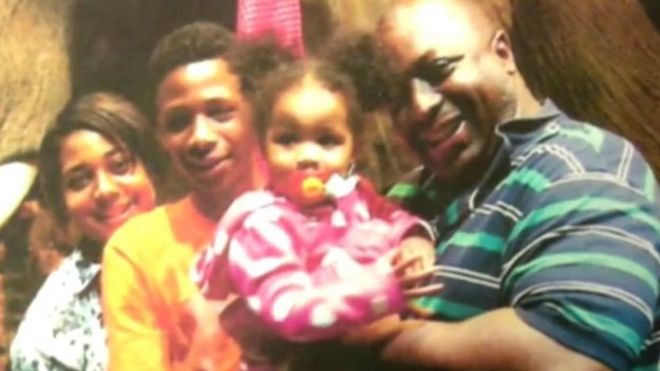

If only we turned our attention on those who are responsible. Had Officer Daniel Pantaleo not choked Eric Garner, the father and husband would be alive today.

Had Officer Pantaleo listened to his pleas, Garner would be alive today.

Had the other four officers interceded, Garner would be alive today.

There is plenty of blame to go around. The NYPD’s embrace of stop-and-frisk policies rooted in the “broken windows” method of policing is a co-conspirator worthy of public scrutiny and outrage.

Yet, we focus on Eric Garner’s choices.

Such victim-blaming is central to white supremacy.

Emmett Till should not have whistled at a white woman.

Amadou Diallo should not have reached for his wallet.

Trayvon Martin should not have been wearing a hoodie.

Jonathan Ferrell should not have run toward the police after getting into a car accident.

Renisha McBride should not have been drinking or knocked on a stranger’s door for help in the middle of the night.

Jordan Davis should not have been playing loud rap music.

Michael Brown should not have stolen cigarillos or allegedly assaulted a cop.

The irony is these statements are made in a society where white men brazenly walk around with rifles and machine guns, citing their constitutional right to do so when confronted by the police.

Look at the twitter campaign “#CrimingWhileWhite” to bear witness to all the white law-breakers who lived to brag about the tale.

Just think about the epidemic of white men who walk into public spaces, open fire and still walk away with their lives. In those cases, we are told we must understand “why” and change laws or mental health system to make sure it never happens again.

Continue reading at BBC News