Book Review | The John Carlos Story: The Sports Moment That Changed the World

Daring Then, Daring Now: The John Carlos Story

Book Review by David J. Leonard | NewBlackMan

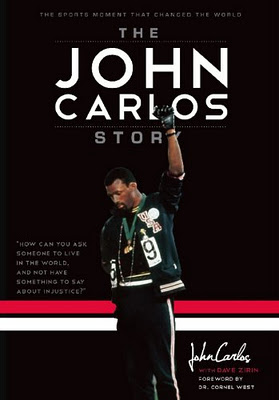

Having studied the 1968 Olympic protest, having conducted an interview with Harry Edwards on the revolt of the black athlete, and being someone dedicated to understanding the interface between sports, race and struggles for justice, I was of course excited about the publication of John Carlos’ autobiography, The John Carlos Story: The Sports Moment that Changed the World. Written with Dave Zirin, the book provides an inspiring discussion of the 1968 Olympics without reducing the amazing life of John Carlos to the 1968 Olympics. More than 1968 or the protests in Mexico City, it chronicles a life of resistance, of refusing to accept the injustices that encompass the African American experience.

John Carlos challenged American racism from an early age. Readers learn of a young man who “went around Harlem handing out food and clothes like Robin Hood and his merry men in Technicolor” (p. 21). Recognizing the level of poverty and injustice in Harlem, and refusing to stand idly by, a young Carlos would break into freight trains to steal food with the purpose of giving it to those who had been swallowed up by the system.

The experience of stealing groceries and good and giving the people something for nothing was positive. Just doing this kind of so-called work opened up my mind and got me to notice what was going on around me. I couldn’t turn my back when I saw evidence of discrimination in the community. I captured it in my mind every time I saw anyone in my neighborhood mistreated by the police (p. 27).

These experiences, like his having to give up on the dream of becoming an Olympic swimmer as a result of societal racism, not only politicized Carlos, but also instilled in him a passion and commitment to help others reach their dreams. It taught about the power and necessity of imagining and fighting for “freedom dreams.”

The John Carlos Story chronicles the ways he has lived a life guided by the philosophy articulated by Fredrick Douglas that “power concedes nothing without demand.” From his organizing a strike at his high school against “the nasty slop they called ‘food’” (p. 33) to his insistence that the manager at the housing protects where he lived address the problem of caterpillars in the courtyard, John Carlos demanded accountability and justice long before 1968.

His book illustrates the level of courage he has shown throughout his life. When the manager refused to address the caterpillar problem, which prevented his mother from joining others in the courtyard because of allergic reactions, Carlos once again lived by the creed: power concedes nothing without demand. John Carlos has lived a life of demanding justice and in the face of refusal demanding yet again. He describes his response in this case as follows:

Then I took the cap off the can and doused the first tree in front of me with gasoline. Then I reached for a box of long, thick wooden matches. After that first tree was soaked, I struck one of the stick matches against my zipper and threw it at the tree and watched. It was a sought: the fire just as that tree like it was a newspaper and turned it into a fireball of fried caterpillars (p. 41).

The compelling life that Carlos and Zirin document extends beyond his youth further reveals a life dedicated to justice. His refusal to accept the racism and the mistreatment experienced while living in Texas encapsulates how America’s racism and systematic efforts to deny both the humanity and citizenship of African Americans compelled Carlos’ activism as a young man and ultimately as an Olympian.

The protest at the 1968 Olympics should not be a surprise given the racial violence experienced by Carlos and his brothers and sisters throughout United States (and the world at large).

Continue reading @ NewBlackMan: Book Review | The John Carlos Story: The Sports Moment That Changed the World.