References to interdisciplinarity or interdisciplinary work have become commonplace within today’s university. Not only erasing the complex and contentious history, its usage has become part of a lexicon that seeks to celebrate work that “transcends” the borders and boundaries of a discipline (& in turn reinscribing TRADITIONAL disciplines as authentic and most desirable).

Despite its usage, or ubiquitous misuse, much of the discourse around interdisciplinarity fails to account for actual interdisciplinary work; it ignores the spaces, and the people who have carried out interdisciplinary projects that are less invested in a particular cannon, a set of theories or methods, or way or thinking but instead concentrates on understanding and transformations. The failure to acknowledge, support, and invest in scholars who are at the forefront (and crossroads) of interdisciplinary work demonstrates the persistence of siloed/disciplinary thinking.

In her new book, Dr. Shana L. Redmond talks the “interdisciplinary mantle” back. In breaking tremendous ground, and in highlighting diasporic histories, the transformative possibilities of the sonic, and the role of music in the formation of imagined (and real) communities, all while demonstrating what interdisciplinary work looks like and the amazing work that can be done through a true embrace of an interdisciplinary praxis, Dr. Redmond delivers a book that is a game changer.

With Anthem: Social Movements and the Sound of Solidarity in the African Diaspora (NY Press, 2013), Dr. Redmond provides a template for what interdisciplinary work looks (and sounds) like. Bringing together ample historiography (and archival materials), the tools of ethno-musicology, textual analysis commonplace within cultural studies, the literature of diaspora, and social movement theory, Dr. Redmond offers a book that centers music “because it creates collective engagement in performance and contributes to a dense black performance history that continually configures Black citizenship through shared ambitions” (13).

The power of Anthem rests not simply with its profound analysis, the range of anthems that it explores, but Dr. Redmond’s ability to offer robust discussions of the sonic. For example, in her discussion of “Ol’ Man River,” Dr. Redmond provides readers with ample background, offering insights into the historic moment of production, the biography of Paul Robeson, and the song’s textual/performative significance, all while demonstrating the power in discussing sound/musicality. “All of Joe’s musical entries are in this key, making Joe phonically and making him the human equivalent of the unadorned CM key – plan and bare. The composition changes in measures 25 to 33 to a solid chord accompaniment with prevalent augmented chords leading the ear to anticipate the sonic” (p. 105). This is the kind of depth of analysis and the range of approaches found in Anthem.

The power of the book rests with its varied (yet dialectical) points of entry – its focus on exploring music, as a “three dimensional document, practice and experience.” As such, it provides a range approaches and analytical frameworks. For example, Dr. Redmond’s discussion of Nina Simone “Four Women” brings into focus the narrative, the representational elements, in these anthems. Here she writes, “Simone confronts the flattening of Black women into one-dimensional objects by addressing intersectional identities of four distinct Black women, all of them representations of women who are at one and the same real and imagined” (p. 185).

Arguing that music provides the basis for an imagined community, creates the tools for agitation, the language of diasporic identity, the historic frameworks, knowledge, the vehicles of movement, and “a method of rebellion, revolution and future visions that disrupt and challenge the manufactured differences used to dismiss, detail, and destroy communities” (p. 1). Music is a movement, and music moves . . . people, history, organization, and communities.

Here, Dr. Redmond builds on Robin D.G. Kelley’s idea of “freedom dreams,” highlighting how sonic performances not only articulate possibilities but also induce change. Sampling Kelley, who described black music as “capable of creating ‘a world of pleasure, not just escape the everyday brutalities of capitalism, patriarchy, and white supremacy but to build community, establish fellowship, play and laugh, and plant seeds for a different way of living, a different way of hearing” (p. 8), Redmond demonstrates a genealogy of diasporic resistance. Pushing back at narratives that confine sonic resistance to movement music, as the “soundtrack” or the musical pulse of movement, that so often positions artists and their creations as the periphery of the real (grassroots, organizationally base) political/material struggles, Dr. Redmond documents the many ways that diasporic anthems have been “absolutely central to the unfolding politics because they held within them the doctrines and beliefs of the people who participated in their performances, either as singers or listening audience.” Evidence here, Anthem engages readers to think about resistance, performance, production and consumption of works that disrupted a white supremacist sonic hegemony.

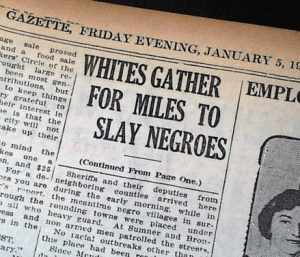

A prominent theme within this book, and many exploring the history of black freedom movements, and black cultural resistance is movement. Amid a history defined by forced stagnation and confinement (slavery, Jim Crow – Sundown towns –, housing segregation, employment discrimination, the prison industrial complex, flattened stereotypes), the history of resistance (and the representations of resistance) has emphasized fluidity, movement, and dynamism. Anthem brings movement into the discussion in profound ways; at one level, the book documents movements, those individuals and their artistic creations who have pushed the community forward, who have resisted the stifling violence of white supremacy. At another level, the book takes readers on a journey throughout the diaspora, demonstrating how the sounds and the struggle of resistance are circulating, moving in and out of different locations, during different moments in history. No song is suck in time; no sound is confined to a certain community or historical moment. Still yet, at another level, Dr. Redmond reveals how these anthems moved people into action while also reflecting the daily moves and maneuvers central to a larger history of resistance. In other words, while the sounds of black freedom movements reveal the shifting “freedom dreams” and the different repertoire of tools available, the anthems, the performances, and the communities resulting from these shared texts were equally powerful as instruments and agents of change.

Dr. Shana Redmond’s Anthem offers an important intervention in how we talk about music, how we talk about diaspora, how we talk about resistance, and how we talk about the dialectics between 6 powerful anthems. Together they “represent a rich variety of perspectives, positions, traditions in African Diasporic history and culture, and through each of them a connection or response between communities is witnessed” (p. 271). And the power is heard, felt, and experienced in the songs themselves, and Dr. Redmond powerful positioning them within a larger history of resistance and the sounds of solidarity.

Postscript

Instead of providing a brief discussion of each anthem, here are the anthems themselves. Listen and then go out and get this book to understand the textual, the sonic, the historic, and the transformative dimensions of each

Questions

- Dr. Redmond notes limits on page 19 – what are these limits and is this unique to music?

- Does the book complicate the idea around “musical genre” or different eras of “music”;

- How does the film complicate if not disrupt the nostalgia afforded to certain artists or music (is there no “post” – 264)?

- What the book tell us about globalization and collective struggle?

- Benedict Anderson argues that newspapers/text are central to formation of nationalist project – imagined communities. How does this book highlight the sonic power for imagined communities?

- What are the shortcomings of seeing music as “soundtrack” or as part of “backdrop” of movements dedicated to material or political change

- In what ways is music textual and performative, individual and collective

- Why do you think hip-hop is peripheral to the narrative yet seemingly central to the discussion of sonic resistance (this is not a critique but a source of praise for a book that offers great insight into hip-hop yet does not center it)