The Failure of Pro-Feminist Hip-Hop

By Mychal Denzel Smith

August 23, 2011

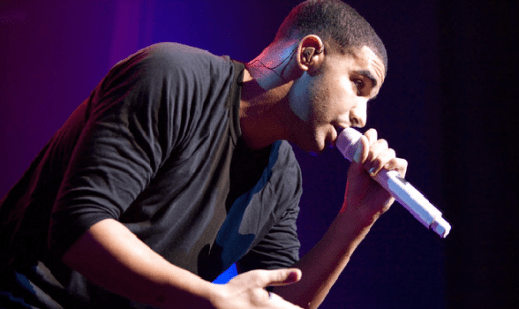

Mychal Smith desperately wants to like pro-feminist hip-hop artist Drake, but something important and powerful is missing from the music.

I often have a very difficult time reconciling my love of hip-hop with all my hoity-toity ideals about gender, sex, and whatnot. However controversial it was, I’m one of those self-proclaimed feminist men who believes, as Gloria Steinem recently said, “It’s really important that kids grow up knowing that men can be as loving and nurturing as women can.” So when I’m listening to some of my favorite rappers exuberantly claim that they “don’t love hoes” or when rape imagery is used by otherwise talented individuals to affirm some sense of manhood and masculinity, I get extremely uncomfortable.

I’m enough of a hip-hop fan to know that this isn’t all the genre and culture have to offer, and I indulge the alternatives with pleasure. But even there, misogyny rears its ugly head at times, and the constraints of masculine identity limit discourse. I could use more parity.

Drake, the Canadian-born teen-TV-actor-turned rapper, is exactly the sort of emcee that a progressive, black, male hip-hop head like myself is supposed to love. He is the antithesis of every tired hip-hop trope revolving around proving your manhood through violence and sexism. He is the type of rapper of whom I should be singing the praises. I should be heralding him as the leader of the new direction hip-hop needs to take so it can grow and evolve its ideas about manhood and masculinity.

I want to love Drake and write essays about how his music opened up a whole new world for me and how it can do the same for others. But I can’t. He and his music do absolutely nothing for me.

Continue reading @ The Failure of Pro-Feminist Hip-Hop — The Good Men Project.