Campus PD: Criminalizing Higher Education?

In what was obviously a slow night television night, I found myself searching for something to watch. After perusing up and down the onscreen schedule, I came across Campus PD (I was somewhat familiar with show having read about their filming in Pullman, WA, where I live), a show that “takes viewers along for the ride with officers on duty to capture firsthand all the mayhem and excitement they take on night after night when student fun spirals out of control.” The show is described in the following way:

From policing parties and security issues, to keeping the peace at sports events and arresting possible suspects, ride with the “Campus PD” as they tackle the ongoing challenge of keeping students safe. Depicting university life from the perspective of the law enforcement professionals who police them, this ground-breaking new series presents a real-life account of these modern-day campus heroes. As they gear up for a shift, these courageous cops know they’re in for a few surprises!

The series heads to five college towns across the country including Tallahassee, FL, San Marcos, TX, Cincinnati, OH, Chico, CA, and Greenville, NC. It takes viewers deep inside the internal lives of the law enforcement professionals policing a town of fun-loving college kids. It isn’t easy, but these dedicated officers love their jobs, and wouldn’t have it any other way.

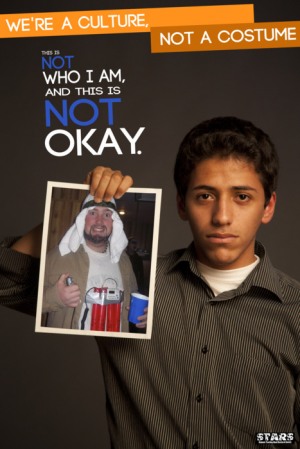

The emphasis on “fun,” “keeping student’s safe” “fun-loving college kids,” parties, and “binge drinking COEDS” is instructive, demonstrating how a show about criminal misconduct goes to great extents to decriminalize its primarily white, middle-class, “participants” and in doing so criminalizes the Other once again.

The show might as well be called “Warning PD.” In the three episodes I watched on television, and countless clips online (which don’t necessarily show the encounters from start to finish leaving it hard to see the final resolution), I have only seen a handful of actual arrests. For the most part, the show brings to life several excessively permissive campus police forces, who tolerate abuse, disrespect, and a culture of chaos. In many instances, college students are given countless warnings, and only after failing to comply with instructions, are they forced to deal with the repercussions of their actions with a ticket or an arrest.

Another common theme within these initial episodes I watched from start to finish was a belief from the students they were unjustly being persecuted by the police. Students would often note that, “they were not doing” anything wrong, or that they were simply engaged in “harmless fun” only to be harassed by campus police. Given the ways in which harassment, racial profiling, and pre-text stops so often define the experiences of youth of color, it is a troubling re-imagination of policing in America. Worse yet, Campus PD does a good job in showing why many college students view police as unfairly harassing them.

In two different episodes (as in the book Dorm Room Dealers), students respond to the presence of police by telling them to go “police” and investigate some real criminals. That is, they were wasting their time with the happenings of college students since they were harmless, as opposed to those who “lived over there.” In both instances, “over there” was clearly the neighborhood inhabited by poor people of color. This assumption (one that is reinforced by the show) that the “real criminals” exist elsewhere reflects the power of American racial and class logic.

According to a study from the Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education, 95 percent of respondents imagined an African American when asked about drug users. In other words, blackness operates interchangeably with criminality, especially in relationship to the urban poor. Better said, “to be a man of color of a certain economic class and milieu is equivalent in the public eye to being a criminal.” (John Edgar Wideman, p. 195)

The consequences of the permissive policing and a culture that imagines college students engaged in criminal activity as just having fun (as opposed to the “real criminals”), is evident in the lack of attention directed at the criminal misconduct taking place at America’s colleges and universities.

According to a 2007 study reported in USA Today, over half of America’s college student regularly abuse alcohol and drugs.

The study found that college students have higher rates of alcohol or drug addiction than the general public: 22.9% of students meet the medical definition for alcohol or drug abuse or dependence — a compulsive use of a substance despite negative consequences — compared with 8.5% of all people 12 and older.

Increasingly, along with the traditionally seen drug and alcohol abuse, college students are abusing prescription drugs like Adderall, termed “smart drugs” by many college students. “For many middle and upper-middle class young people in New York,” notes Lala Straussner. “Adderall is much more acceptable than using methamphetamine (more common on West Coast) or crack cocaine, although the brain doesn’t know the difference.” Yet, the ubiquity and acceptance of “smart drugs” is simply the perceived function or the consequences of these drugs but the ways in which crack and meth are both racialized and connected to distinct class identities. Prescription drugs, on the other hand, are linked to those in college, who are said to have a future, illustrating criminality and criminals are identities are constructed as elsewhere and not within college communities.

While shows like Campus PD illustrate the ubiquity of instances of public intoxication, cases of drunk-driving, and physical assaults, other issues plague college communities. As such, it does little to elucidate the problem of sexual violence (20-25% of women in college will experience rape or an attempted rape), prescription drug abuse, and even drug dealing. The erasure of these systemic problems reflects a culture that imagines college as a space of parties, fun, and adolescent behavior rather than criminal activity.

This type of narrative is evident in the recent drug busts at San Diego Sate University and Columbia University. In 2008, after a several month investigation, authorities arrested 75 students (96 people in total), confiscating drugs worth a total of approximately $100,000 worth of drugs. Among the 20 students arrested for distribution and sales was a criminal justice major, who when arrested was in possession of two guns and 500 grams of cocaine. San Diego County Dist. Atty. Bonnie Dumanis made clear that their investigation demonstrated “how accessible and pervasive illegal drugs continue to be on our college campuses and how common it is for students to be selling to other students.” This was certainly true with Columbia University, where 5 students were arrested as part of “Operation Ivy League,” “a five-month undercover sting, during which police purchased $11,000 worth of drugs from the students out of Columbia fraternity houses and dorms.”

While the media rendered this incidence and that at SDSU as a shocking spectacle, it is clear that the situation at these schools is a national phenomenon. This should actually be surprising given how drug markets are as segregated as the rest of America. According to A. Rafik Mohamed and Erik D. Fritsvold, authors of Dorm Room Dealers, who spent 6-years examining drug distribution at a Southern California Private school, not only do students sell to other students, but do in a reckless manner, which in their mind highlight a sense of entitlement based on the students’ middle-class white identities. Phillip Smith describes their findings in “Dorm Room Dealers: A Peek into the Drug World of the White and Upwardly Mobile”:

Mohamed and Fritsvold show repeatedly the reckless abandon with which their subjects went about their business: Dope deals over the phone with uncoded messages, driving around high with pounds of pot in the car, doing drug transactions visible from the street, selling to strangers, smuggling hundreds of pills across the Mexican border. These campus dealers lacked even the basics of drug dealer security measures, yet they flew under the radar of the drug warriors.

Even when the rare encounter with police occurred, these well-connected students skated. In one instance, a dealer got too wasted and attacked someone’s car. He persuaded a police officer to take him home in handcuffs to get cash to pay for the damages. The cop ignored the scales, the pot, the evidence of drug dealing, and happily took a hundred dollar bill for his efforts. In another instance, a beach front dealer was the victim of an armed robbery. He had no qualms about calling the police, who once again couldn’t see the evidence of dealing staring them in the face and who managed to catch the robbers. The dealer wisely didn’t claim the pounds of pot police recovered and didn’t face any consequences.

A former Columbia student highlights a similar culture there, adding more evidence to the arguments offered in Dorm Room Dealers.

But, in fact, the prestigious institution on Manhattan’s Upper West Side has long been “ripe” for drug trafficking, a knowledgeable 2009 Columbia graduate told The Daily Beast. “I think the permissive environment of Public Safety”—as Columbia’s campus police force is known—“makes it a no-brainer proposition,” said this former student, who described himself as a recreational drug user who dabbled in selling. “I always felt safe.”

The culture and climate of Columbia in terms of public concern and policing, as opposed to the levels of surveillance found a few miles away in Harlem, tells an important story about how race and class operate in contemporary America. Campus PD offers a similarly distorted glimpse a crime as well.

Media accounts of these two recent drug operations and shows like Campus PD have done little to shine a spotlight on the double standards that exist between the primarily white middle-class student population and poor youth of color when it comes to policing and incarceration. With the situation at Columbia, one student has plead guilty thus far; although charged with the most serious crimes, he was sentenced to 6-months in prison in July. In a city where 46,500 people were arrested for marijuana possession in 2009, with 87% of these people being black and Latino, the inequality is quite clear.

San Diego saw a similar outcome, with many of those arrested pleading guilty only to face probation and entrance into a drug diversion programs, leading some people to question why police are spending so much time and energy conducting investigations against college students that do not result in incarcerations. When considering the media coverage, popular representations of college campuses, levels of policing and unzealous prosecution, it is no wonder that while African Americans constitute 13% of all monthly drug users, they represent 38% of these arrested for drug possession, 55% of convictions and 74% of prison sentences; it is as argued by Michelle Alexander, the new Jim Crow, ostensibly cordoning off America’s college and universities from policing and prosecution. The criminalization of black and brown youth and the decriminalization of white America, particularly its middle-class college-bound constituency, have material consequences.

Evident in a show like Campus PD and the various examples provided here is the ways in which “what it means to be criminal in our collective consciousness to what it means to be black.” In other words, “the term black criminal is nearly redundant . . . . To be a black man is to be thought of as a criminal, and to be a black criminal is to be despicable – a social pariah” (Alexander 2010, p. 193). No wonder so many students yell at cops to go focus on the “real criminals”; that is the message they have learned all too well.

***